the modern city-state was founded in 1819 as a British colony to the developed, independent country it is today. Urban planning is especially important due to land constraints and its high density.

the modern city-state was founded in 1819 as a British colony to the developed, independent country it is today. Urban planning is especially important due to land constraints and its high density.The Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) is Singapore's national land use planning authority. URA prepares long term strategic plans, as well as detailed local area plans, for physical development, and then co-ordinates and guides efforts to bring these plans to reality. Prudent land use planning has enabled Singapore to enjoy strong economic growth and social cohesion, and ensures that sufficient land is safeguarded to support continued economic progress and future development.

History

Initial planning

The founding of modern Singapore in 1819 by Sir Stamford Raffles was arguably a planning event in itself, as it involved the search for a deep, sheltered harbour suitable to establish a pivotal maritime base for British interests in the Far East. This was also to protect her maritime trading routes on the East-west axis. Hence, the settlers found the waters of Keppel Harbour suitable, and the entourage of eight ships anchored off the mouth of a small river on January 28 1819. Raffles made landing on the north bank of the river, and discovered favourable conditions for the setting up of a colony. The area on the side of the river's north bank which he was on was level and firm, although the southern bank was swampy. Abundant fresh water was found, and the river itself was a sheltered body of water protected by the curved river mouth. This river was to become the nexus from which the new colony would thrive, and the immediate surrounding areas would form the core of the island's business and civic areas.

Upon its formal establishment with the signing of a treaty on February 6 the same year, Raffles left the settlement, leaving Colonel William Farquhar as the first Resident of Singapore. By the end of May, Raffles returned, and while noting the rapid development of the city, realised the need for a formal urban plan to guide its otherwise disorganised physical expansion. He left the colony again, instructing Farquhar to designate residential, commercial, and governmental land uses for the colony.

When he returned more than two years later in October 1822, however, Raffles was dismayed by the way the colony had grown. He therefore formed a Town Committee headed by Lieutenant Philip Jackson to draw up a formal plan for the colony, which came to be known as the Jackson Plan, and was to become the first detailed city plan for Singapore. This plan was to lay the groundwork of the city's street and zonal layout, the essence of which continues to exist today. For example, the allocation of civic institutions on the north bank of the Singapore River and the creation of the main commercial area in what was then known as "Commercial Square" on the south bank has today evolved into the Civic district and the CBD on either side of the river. The grid-like street pattens continue to exist, while the ethnically segregated residential zones, despite having been largely depopulated by now, have continued to exist as ethnic enclaves attracting the attention of tourists, such as in the Chinatown, Little India, and Kampong Glam districts.

Post-Raffles

Raffles's foresight and well-intended efforts to maintain orderliness in the city's growth started to spiral out of control just eight years after the Jackson Plan was drawn up. With no updates and no new plans drawn up by the British, the city soon outgrew itself, and the plan soon proved completely inadequate. When Raffles arrived in 1819, the population numbered about 150. By 1911, this figure had mushroomed to 185,000, resulting in severe overcrowding, particularly in the Chinatown area. The road system, planned for travel by foot and horse carts, also could not handle the exploding traffic, particularly when motorised vehicles came to Singapore en masse in the 1910s. The 842 private cars in 1915 had multiplied to 3,506 by 1920.

With the severe overcrowding in the city centre, the population, particularly the better-off, started to move into the suburbs. The better-off families moved especially to the East Coast, where they often operated plantations and maintained large sea-side homes near the beach at Katong. Several wealthy Malay families were to leave a legacy in the area through their family names, including those of Aljunied and Eunos. Less well-off families tended to move into the southern parts of the island as a natural extension of the Chinatown area. Subsequently, however, they also moved into other areas, including the East Coast, spreading the problems of overpopulation to the suburbs with the creation of squatters. This growth also resulted in suburban roads becoming congested by traffic, particularly along Geylang Road which leads to the East Coast.

Public Housing

In 1927, the colonial government attempted to arrest the situation by setting up the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT), with the main aims of alleviating urban congestion and the provision and upgrading of public infrastructure, particularly in the widening of roads to accommodate rising and modernising traffic. Their efforts were evident only in localised areas, as the body did not have the legislative power to produce comprehensive plans or to control urban development. The Second World War also disrupted their efforts during the Japanese occupation from 1941 to 1945.

Singapore emerged from the war in physical ruins and with a large number of homeless residents. A Housing Committee was thus formed quickly in 1947, and reported an acute housing shortage facing the city, where the population had already reached a million by 1950. With 25% of the population living in 1% of its land area, and with some shophouses housing over 100 people, the SIT's efforts were clearly inadequate in its attempts to rehouse the population into new multi-story apartment blocks.

Under the People's Action Party, which came into power when it won the 1959 Elections of Singapore, the Housing Development Board was founded in 1960, replacing the Singapore Improvement Trust. This proved to be the turning point in the history of modern Singapore. Within five years, the HDB had constructed more than 50,000 housing units, which was several times more than the SIT had constructed within the time span of more than 20 years. Within the 1970s, most of the population had found adequate housing. Most of the current urban planning policy is derived from the practices of the HDB.

Flats 10-15 storeys high were initially built. With time, they reached over twenty and thirty storeys, and at present, fifty-story housing complexes are under construction.

Current policy

The current policy of Singapore's urban planners who come under the Urban Redevelopment Authority is to create partially self-sufficient towns and districts which are then further served by four regional centres, each of which serves one of the four different regions of Singapore besides the Central Area. These regional centres reduce traffic strain on Singapore's central business district, the Central Area, by replacing some of the commercial functions the Central Area serves. Each town or district possesses a variety of facilities and amenities allocated strategically to serve as much as possible on at least a basic scale, and on the regional scale, an intermediate one. Any function of the Central Area not served then is allowed by the regional centre to be executed efficiently as the transport routes are planned to link up the regional centres and Central Area effectively. The Housing Development Board works with the Urban Redevelopment Board to develop public housing according to the national urban planning policy.

As land is scarce in what is the most densely populated country, the goal of urban planners is to maximise use of land efficiently yet comfortably and to serve as many people as possible for a particular function, such as housing or commercial purposes in high rise and high density buildings. Infrastructure, environmental conservation, enough space for water catchment and land for military use are all considerations for national urban planners.

Land reclamation has continued to be used extensively in urban planning, and Singapore has grown at least 100 square kilometres from its original size before 1819 when it was founded. The urban planning policy demands that most buildings being constructed should be high-rise, with exceptions for conservation efforts for heritage or nature. A pleasant side effect is that many residents have pleasant views. Allocating primary functions in concentrated areas prevents land wastage. This is noticeable in Tampines New Town in comparison to the housing blocks found in Dover. Housing blocks turned into complexes, which occupied a large area with thousands of apartments in each one as opposed to smaller high-rise blocks with hundreds. This allows for efficient land use without compromising the standard of living.

Urban planning policy also relies on the effective use of public transport and other aspects of Singapore's transport system. Singapore's Mass Rapid Transit system allows the different districts to be linked by rail to all the other districts without having to rely on roads extensively. This also reduces strain on traffic and pollution while saving space. The districts with their different functions are then allocated strategically according to 55 planning areas.

Post-independence Singapore government, with the exception of public housing in Chinatown, has largely shied away from allocating too much housing in the Central Area and especially the Downtown Core, but with increasing density and land reclamation in Marina South and Marina East, there are current plans for new public housing close to the Downtown Core.

Singapore's land is increasingly crowded, and hence the placement of a district of one function that obstructs more infrastructure development in that area (such as building an expressway tunnel or a rail line), as opposed to the placement of a district of a different function that would accommodate future infrastructure, has become increasingly likely. A district of one function could be inefficient if it does not have proper access to another district of another function, or on the other hand, if it is too close. Public amenities have to be strategically placed in order to benefit the largest number of people possible with minimum redundancy and wastage. A major feature of urban planning in Singapore is to avoid such situations of land wastage.

Article Source: www.absoluteastronomy.com/topics/Urban_planning_in_Singapore

The real estate industry has always been one of trends. One only needs to look back over the years to readily identify the numerous trends that have asserted themselves at different times. One of the more recent trends that we have seen is many younger professionals leaving the city for the suburbs. This is partly due to their want to raise children in a more sheltered atmosphere and because of rising property values within the urban core. Conversely one of the newer trends that we are experiencing is the baby boomers who are now mainly empty nesters are buying property in the urban core to get away from higher maintenance homes and into areas with a lot of extra assets and convenience.

The real estate industry has always been one of trends. One only needs to look back over the years to readily identify the numerous trends that have asserted themselves at different times. One of the more recent trends that we have seen is many younger professionals leaving the city for the suburbs. This is partly due to their want to raise children in a more sheltered atmosphere and because of rising property values within the urban core. Conversely one of the newer trends that we are experiencing is the baby boomers who are now mainly empty nesters are buying property in the urban core to get away from higher maintenance homes and into areas with a lot of extra assets and convenience. This move has, of course freed up a number of suburban homes to fulfill the needs of the younger generation that is seeking to leave the city to do as their elders did 30 years ago. The benefit of this is that there are already a number of homes that have been specifically designed for the raising of families. Essentially it is a win-win situation all around. What will be really interesting to see is if the pattern repeats itself in another 20 years or so. We only have to wait and see what the future trends will be.

This move has, of course freed up a number of suburban homes to fulfill the needs of the younger generation that is seeking to leave the city to do as their elders did 30 years ago. The benefit of this is that there are already a number of homes that have been specifically designed for the raising of families. Essentially it is a win-win situation all around. What will be really interesting to see is if the pattern repeats itself in another 20 years or so. We only have to wait and see what the future trends will be. Thanks to its external free-standing structure, ISLAND requires no other brick or reinforced concrete structures. The tank contains all the components of the “Island” system making it a unique sturdy sheet plate structure with strengthened attachment points for the hydraulic lifting system.

Thanks to its external free-standing structure, ISLAND requires no other brick or reinforced concrete structures. The tank contains all the components of the “Island” system making it a unique sturdy sheet plate structure with strengthened attachment points for the hydraulic lifting system.

According to the DFID report, about one-fifth of the entrants in the urban labor force come from rural areas. In spite of their economic fragility, most of these workers manage to send or take a large portion of their meagre wages back to their rural families. A recent report estimated that the approximately 100 million rural residents who work away from their villages sent or carried home a total of 370 billion CNY (about thirty-five billion USD) in 2003, an increase of 8.5% from the previous year. Estimates of the amount sent/brought back by migrant workers range from between three and four thousand CNY.

According to the DFID report, about one-fifth of the entrants in the urban labor force come from rural areas. In spite of their economic fragility, most of these workers manage to send or take a large portion of their meagre wages back to their rural families. A recent report estimated that the approximately 100 million rural residents who work away from their villages sent or carried home a total of 370 billion CNY (about thirty-five billion USD) in 2003, an increase of 8.5% from the previous year. Estimates of the amount sent/brought back by migrant workers range from between three and four thousand CNY. Durham's newly adopted comprehensive plan is underutilized, often misinterpreted, and is overly complicated, which renders it more than useless, because we delude ourselves into thinking that because we have this plan, we are building a better community for the general welfare of the citizens, when in fact we most often ignore the plan and how it affects people. That is the social aspect that gets ignored most often, which is the first thing mentioned in those definitions of planning and of what planners do.

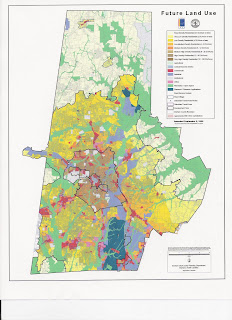

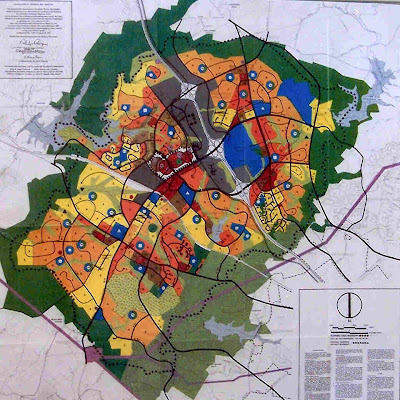

Durham's newly adopted comprehensive plan is underutilized, often misinterpreted, and is overly complicated, which renders it more than useless, because we delude ourselves into thinking that because we have this plan, we are building a better community for the general welfare of the citizens, when in fact we most often ignore the plan and how it affects people. That is the social aspect that gets ignored most often, which is the first thing mentioned in those definitions of planning and of what planners do.  A second issue about plans, including the one in Durham, can be seen in the map itself. Look at the map. It is very pretty. It shows where the roads go, or where they ought to go. It shows where the houses go or ought to go, apartments should go, as well as shopping centers (often in red), parks and schools, flood plains, and open space.

A second issue about plans, including the one in Durham, can be seen in the map itself. Look at the map. It is very pretty. It shows where the roads go, or where they ought to go. It shows where the houses go or ought to go, apartments should go, as well as shopping centers (often in red), parks and schools, flood plains, and open space.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "sprawl" first appeared in print in this context in 1955, in an article in the London Times that contained a disapproving reference to "great sprawl" at the city's periphery. But, as Bruegmann shows, by then London had been spreading into the surrounding countryside for hundreds of years. During the 17th and 18th centuries, while the poor moved increasingly eastward, affluent Londoners built suburban estates in the westerly direction of Westminster and Whitehall, commuting to town by carriage. These areas are today the Central West End; one generation's suburb is the next generation's urban neighborhood. As Bruegmann notes, "Clearly, from the beginning of modern urban history, and contrary to much accepted wisdom, suburban development was very diverse and catered to all kinds of people and activities."

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "sprawl" first appeared in print in this context in 1955, in an article in the London Times that contained a disapproving reference to "great sprawl" at the city's periphery. But, as Bruegmann shows, by then London had been spreading into the surrounding countryside for hundreds of years. During the 17th and 18th centuries, while the poor moved increasingly eastward, affluent Londoners built suburban estates in the westerly direction of Westminster and Whitehall, commuting to town by carriage. These areas are today the Central West End; one generation's suburb is the next generation's urban neighborhood. As Bruegmann notes, "Clearly, from the beginning of modern urban history, and contrary to much accepted wisdom, suburban development was very diverse and catered to all kinds of people and activities."